Julia Storch

DIG340

Professor Annelise Shrout

February 19th, 2016

Women, Well;

An Analysis of Gender Expectations and Automobile Technology

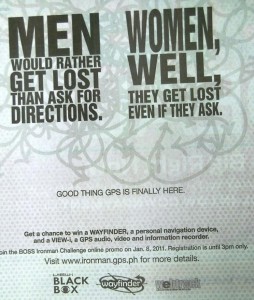

The GPS, or Global Positioning System, was originally developed by the military. Work with NASA and the DOD eventually lead to the creation of a DNSS (Defense Navigation Satellite System) so that all military organizations could contribute to the research. The GPS satellite technology can serve an unlimited amount of people – a theoretically equalizing and ungendered technology. The GPS, however, when used commercially, has typically been used in cars, a technology with a long history of intricate gender relations. This advertisement is restating age old gendered stereotypes: that women are bad drivers and men are incapable of asking for help. First, I will look at how women have been excluded from car technology since cars first appeared on the market and why driving continues to be coded masculine, and then I will examine the stereotype of the hyper masculine man who refuses to ask for help. The adverse effect of the patriarchy on men and the long history of excluding women from technological fields manifests itself into this artifact, making it a perfect example of the intersection of gender and technology.

Car ownership grew rapidly in America after the advent of mass production, but in the beginning there were very few women drivers. Margaret Walsh notes “the motor car was perceived to be a piece of masculine machinery which was difficult and dirty to drive and was beyond the capability and fastidiousness of women to operate.”[1] At this point, even working women were expected to not drive and all women only operated domestic machinery, such as washing machines and vacuum cleaners. There were exceptions; some women undertook transcontinental car journeys and publicized that women were just as competent drivers as men, but the cult of domesticity remained in place. Women also never entered the public eye as automobile builders; the job was considered too dirty and dangerous for women. Wajcman generalizes about the absence of women from technology, saying that it “was a consequence of the male domination of skilled trades that developed during the Industrial Revolution.” [2] But as time went on and families became more auto-centric, women would eventually become drivers in greater numbers.

One reason for this was that women began enter the American workforce in greater numbers in the 1960s and 1970s, and they needed cars to get to their jobs. Still, their access to cars was not the same as men, as they were paid less than men. There were also cultural assumptions about why men drove. As one historian writes, “[men] got behind the wheel to experience independence, recklessness, and mastery of the car and the road. The car became part of the male identity; its power, technological superiority, and performance was often conflated with the man who drove it. Women, on the other hand, drove cars not for the excitement they might provide, but simply as a means to perform prescribed tasks and fulfill gendered roles.”[3] In order to reserve this masculine space, women can only find their niche within the car industry in “woman cars” or “chick cars” which represent maternity and female vanity respectively. A separation of spheres enters the conversation; women can have cars, but only to be better mothers and wives, enforcing the segregation of interests and lifestyles.

The theory of separate spheres is mentioned by Joan S. Scott and described as an effect that endorses “a certain functionalist view ultimately rooting in biology and to perpetuation the idea of separate spheres (sex or politics, family or nation, women or men) in the writing of history.”[4] Traditionally, separate spheres refer to the idea that women had power in the home, while men had power in public. There is a history of social-scientific writing “addressing the public spheres of work and politics as being of fundamental importance, and as separate from domestic relations.”[5] As the car entered the market, it acted as a conduit between the home and the public. Because of separate spheres, men could use the car to assert their public dominance. Men and their experience were treated as the norm, so everyone accepted the growth of the automobile industry without looking at why women were driving less or driving different cars. The theory of separate spheres only holds true for rich, urban, Western families, which fits appropriately the introduction of automobiles, since those were, and still are, most easily available to this demographic. Women drove to taxi their kids to work or to go shopping, remaining within their sphere of domesticity. Since women became drivers later than men and cars represent the public sphere, it has been hard for female drivers to be taken seriously.

“Men would rather get lost than ask for directions,” this advertisement claims. Why do men hesitate to ask for help? There is an association between needing help and showing weakness, and the patriarchy has taught men that signs of weakness are unacceptable. Men must always be confident and secure in their decisions – a manifestation of hypermasculinity. In order to minimize the questioning of the patriarchy, it needs to establish that men should be in control and hold all the power. If men are seen as fallible, they will undermine the patriarchy’s attempt to frame men as better than women. This ends up hurting men, as they are taught that they cannot show emotion or any feminine (weak) traits. Asking for help is a betrayal of the cultural assumptions placed upon men by the patriarchy. In addition, Massanari writes, a facet of hypermasculinity is “valorizing intellect over social or emotional intelligence.”[6] Valuing intellect partially explains the culturally driven desire for men to always be right.

Intelligence becomes important when it comes to driving, a realm in which men must be particularly masculine. Look at any cultural depiction of an auto shop, and find aggressive, tough, sexist caricatures of men. The winner of the Formula One Grand Prix is sprayed with champagne as he stands next to scantily clad women – women who are noticeably absent among the racers themselves. The muscle car has become a symbol of masculinity, tying back to the idea that men drive to experience recklessness and enjoy themselves, while women drive to fulfill tasks. In order to show other men how well they perform masculinity, men have inculcated themselves with knowledge about cars – while women need only know the make of their car, men pride themselves on knowing about things like horsepower and the specific technology and mechanics of cars. One cultural expression of this is the tendency of auto mechanics (usually male) to address the man when explaining auto repairs. It is assumed that women do not know enough about cars to understand, or even that they do not care to understand.

The cultural assumption this advertisement makes is that women can ask for help, even if they are intellectually incapable of following it, while men get themselves lost because they are afraid to seem weak. The advertisement is perpetuating these ideas, reminding readers of their gendered expectations and what their relationship with cars should be. Artifacts such as this one are not unusual to find in current American society, as these attitudes regarding men and women are still prevalent in the cultural framework.

[1] Walsh, Margaret. “Gendering Mobility: Women, Work And Automobility In The United States.” History 93.311 (2008): 376-395. America: History & Life. Web. 18 Feb. 2016.

[2] Wajcman, Judy. “Male Designs on Technology.” TechnoFeminsim. 2004. Print.

[3] Lezotte, Chris. “The Evolution Of ‘The Chick Car’ OR: What Came First: the Chick or the Car?. Journal Of Popular Culture. (2012): 516-531. Historical Abstracts. Web. 18 Feb. 2016

[4] Scott, Joan W. “Gender: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” Feminism and History. 1996. Print.

[5] Wajcman, Judy. “Male Designs on Technology.” TechnoFeminsim. 2004. Print.

[6] Massanari, Adrienne. “#Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures.” New Media and Society. Web. 18 Feb. 2016.

Works Cited

Kaplan, Elliott D. Understanding GPS: Principles and Applications. Boston: Artech House, 1996. Web. 19 Feb. 2016.

Lezotte, Chris. “The Evolution Of ‘The Chick Car’ OR: What Came First: the Chick or the Car?. Journal Of Popular Culture. (2012): 516-531. Historical Abstracts. Web. 18 Feb. 2016

Massanari, Adrienne. “#Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures.” New Media and Society. Web. 18 Feb. 2016.

Scott, Joan W. “Gender: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” Feminism and History. 1996. Print.

Wajcman, Judy. “Male Designs on Technology.” TechnoFeminsim. 2004. Print.

Walsh, Margaret. “Gendering Mobility: Women, Work and Automobility In The United States.” History 93.311 (2008): 376-395. America: History & Life. Web. 18 Feb. 2016.